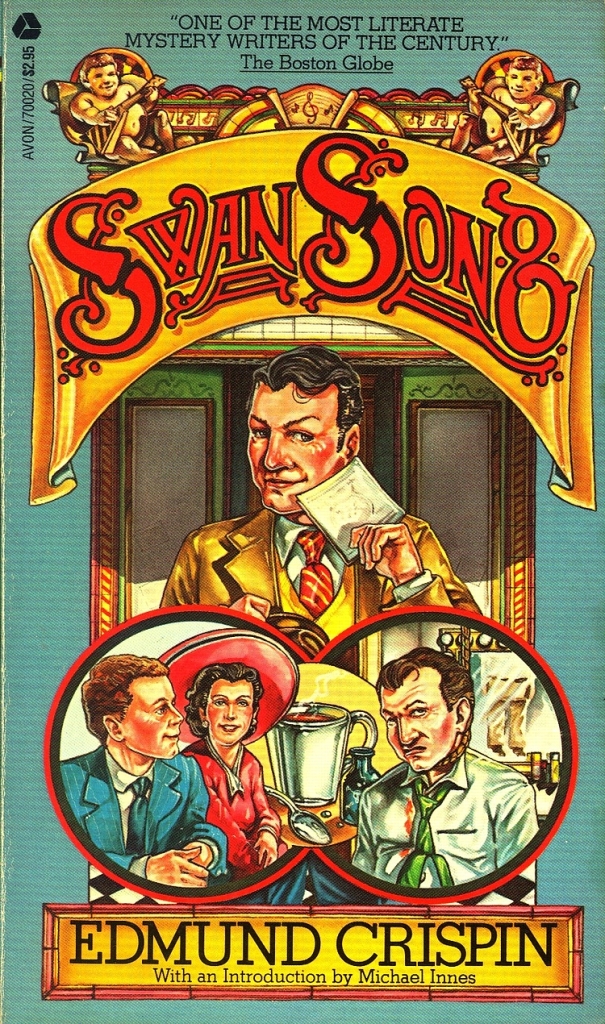

I have tried for so long to get into opera. So much of it is beautiful music, and there are so many engrossing stories to tell. But there are only a select few works – Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Ravel’s L’Enfant et les sortilèges, and Adams’ Nixon in China to name some – that have actually imprinted themselves on my mind. Maybe it’s because I just prefer the instrumental grandeur of the symphony orchestra to vocals, or that as someone who has spent much time playing in orchestras, it comes more naturally to me when there is no singing involved. Maybe it’s because so many operas are in languages I don’t understand, which makes listening to it without an accompanying video and subtitles a bit awkward. But the fact remains, that I simply do not know opera the way I know the orchestra. This gave Edmund Crispin’s Swan Song an interesting allure for me, because it was set in this world which I have long felt on the precipice of but still know so little about. While perhaps its view of the opera and those people associated with it was somewhat jaded, there is no doubt in my mind that Swan Song is one of the most entertaining and solid mysteries I’ve read in a long time.

The novel begins with a short prologue detailing the courtship of Elizabeth Harding, a crime writer, and Adam Langley, a famous British opera singer. They meet during a production of Der Rosenkavalier as Elizabeth studies the production for an upcoming project. Although she is immediately attracted to Langley, it is not Langley who reciprocates these feelings at first but rather one Edwin Shorthouse – a fellow leading man in the production and friendly rival of Adam’s. Ultimately, Elizabeth is able to avoid Shorthouse’s smarminess and get Adam to love her back. Shorthouse makes his newfound hatred of Adam known but quickly reconnoiters on it, opting for peace instead. And so, they all find themselves together again for England’s first post-WWII production of Wagner’s 4.5-hour long comedy, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

Tensions immediately rise at Die Meistersinger‘s rehearsals. Shorthouse constantly fights with the conductor, an up-and-comer named Peacock, to the point that it seems like one of them will be forced to leave – and just about everyone would prefer it be Shorthouse, who has already attempted to rape a member of the chorus named Judith Haynes. It is no great loss, then, to the cast and crew of this Wagner production when Edwin Shorthouse is found dead, having apparently hanged himself in his dressing room in a drunken stupor. The only surprise is that he killed himself before someone else could. But of course, this is a murder mystery, and when Oxford don Gervase Fen comes on the scene, he thinks otherwise.

Something that quickly struck me about Crispin’s writing is just how readable the prose is. It’s not simplistic or anything, and there were certainly instances where a word was esoteric enough to warrant a Google search, but the way he writes with a perfect balance of humor, seriousness, academic instruction, and suspense kept me hooked without pause. I read this book in only four days, and I don’t think I’ve read a book that quickly since Whistle Up the Devil back in August… and I’ve read quite a few books since then (including what I don’t review on the blog.) There is an ease with which he both blends and switches between tones, whether it be situationally or through dialogue. What helps in this too is that Crispin’s characters are all interesting, and not just one-noted or reliant on a sole characteristic like in so many other GAD novels. While many of the suspects fit into the general zeitgeist of operatic and bohemian decadence, they have their own scruples and peculiarities which make them stand out. Joan Davis, another co-star of Die Meistersinger, for instance, can easily switch between cold indifference and warmhearted caring for one person or the other, depending on the situation. Charles Shorthouse, Edwin’s composer brother, has the energy of a somewhat crazed artist, but shows moments of surprising lucidity. What helps the development of the characters is Crispin’s willingness to switch (third person) perspective between most of the major characters in the novel, and not just the main investigative force comprised of Fen, Langley, Sir Richard Freeman of Scotland Yard, and Inspector Mudge. The switches between the actions of various suspects helps to keep up intrigue, as many of their actions can be taken as either benign or deceitful.

The pacing and characterizations dovetail beautifully with the setting Crispin has created for his story: a fictional opera house built in the middle of an Oxford campus. Although the building itself is described in detail so as to help illuminate certain aspects of the investigation, the way the setting is so amusingly realized has to do with the general emotional temperature of the production itself, and how the characters interact with it. Crispin shows his disdain for the common opera singer right of the bat with the novel’s opening sentence:

There are few creatures more stupid than the average singer.

Swan Song, Chapter 1

and he continually proves this thesis as the various performers in Die Meistersinger make poor decisions in many ways. Shorthouse of course is the prime example, with his lechery, bullying, and alcoholism… although the level of gossip and backhandedness the others exhibit adds further to this. However, what really solidified the atmosphere for me were the more mundane, and often humorous, details that Crispin adds to round out the more melodramatic interactions between the major players, such as these perfectly crafted vignettes of the opera orchestra warming up before the dress rehearsal:

In the orchestra-pit, a trombonist was doing a very creditable imitation of a Spitfire diving, and a clarinetist was surreptitiously playing jazz.

A few newcomers drifted in and uttered reluctant apologies to Peacock. The tuba player arrived, unpacked his instrument, and began making a sound like a fog-horn on it, while the rest of the orchestra chanted “Peter Grimes!” in a quavering, distant falsetto.

“I think,” said Peacock as he contemplated this phenomenon, “that perhaps wed’ better start.”

The first oboe had not even yet appeared, and Peacock, from the rostrum, periodically supplied his part by a hollow, sepulchral chanting which greatly disconcerted everyone.

Swan Song, Chapters 14-15

Perhaps as someone who has the experience to understand the quirks and habits of orchestra musicians (I am only a music major though, so do not mistake my opinions for that of a professional), these scenes made more of an impression than for other readers, but it was very easy to imagine myself in the midst of a group of musicians who, although we do not get to know them well in the course of the novel, must certainly know one another quite well and have, in the course of professional life, become a bit more laid-back. Crispin, the pseudonym of British film composer Bruce Montgomery, would be well versed in the mannerisms of musicians. With an attention to detail like this, Crispin elevates Swan Song from just another mechanical Golden Age mystery novel to something more akin to the overall British literary tradition (Michael Innes in his introduction to the book compares Crispin’s earlier Holy Disorders to a Dickensian adventure.)

And obviously, I am glad that Crispin gave a shout-out to the trombones in a novel about an opera with great trombone parts, something very refreshing after When the Wind Blows and its orchestra program sans low brass.

Of course, none of these novelistic qualities really matter unless the mystery plot itself is solid. Thankfully, it is that and more. Edwin Shorthouse’s murder is always puzzling, with a steady investigation of both physical/forensic clues and the persons connected to Shorthouse who may have had the means, motive, or opportunity to kill him. Although there is not much emphasis on it, this is a locked-room mystery: Shorthouse is found dead by Langley around 11:30 pm one night, in his dressing room. Shorthouse had met a member of the chorus there around 11 pm for a few minutes, and according to the medical examiner could not have been hanged earlier than 11:25. In all that time the only door to the dressing room was watched by a trustworthy security guard, and the sole window – a skylight – is only large enough for a hand or a bird to fit through, not enough space to correctly fit a noose around someone’s neck. Fen prefers to investigate Shorthouse’s interpersonal affairs and alibis, but nonetheless picks up on a line of reasoning that leads to how the murderer manages to hang Shorthouse in such circumstances. It is a solution that rests more on the technical side of things but is nonetheless fascinatingly constructed. A second murder late into the game adds to the intrigue, and ultimately the plethora of motive and vitriol leads to a satisfactory solution. The motive itself is not all that surprising, considering that everyone has a clearly stated reason to want Shorthouse dead, but the trick behind the murderer’s identity was hidden well; I have seen this trick done once before, and it was more shocking in that prior work, but the solution felt nonetheless justified.

Now, has reading Swan Song convinced me to dive deeper into opera? Well, I don’t know if this experience was a direct catalyst, but I am currently listening to a live broadcast of the Met Opera while typing this up, a week after auditioning for a local opera orchestra (where, alas, I did not advance to the second round.) Coincidentally, I am also performing the overture to Die Meistersinger in a concert in a few weeks. Maybe it was part of the jolt I needed to make the leap, who knows. What I can say for sure is that this is one of the best GAD works I’ve read in probably the past year in terms of the literary and mystery quality, and I am very excited to read more Crispin.

New Horizons Challenge: 17 works out of 25

Author: Edmund Crispin

The Challenge Requirements so far:

2/3 works translated into English

4/3 works written in English after 1970

3/2 works that are hardboiled or noir

2/2 works written by an American minority author

2/2 works with a musical setting

Other Reviews:

Ah Sweet Mystery!, Cannonball Read 5, crossexaminingcrime, Ela’s Book Blog, gadetection, The Grandest Game in the World, The Green Capsule, In Search of the Classic Mystery Novel, In so many words, The Locked Room, The Reader Is Warned, Vulpes Libris

2 responses to ““Swan Song” by Edmund Crispin”

Well, you won’t find much orchestral interest in a lot of Italian opera. Listen to Wagner (there are glorious things in the Ring and Parsifal, despite their paralysing longueurs) and Strauss (especially Salome and Elektra, then perhaps Die Frau ohne Schatten). Listen to Berlioz’s Troyens, Meyerbeer’s Huguenots, and to the operas of Massenet. Listen to the Russians (Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, anything by Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin’s Prince Igor) and to the Slavs (Dvorak, Smetana).

Which Met broadcast?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the recommendations! I’m definitely more familiar with Wagner since there are a good deal of trombone excerpts of his but the only one I’ve listened to all the way through was Tristan.

The broadcast was X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X.

LikeLike